Every morning as you groggily enter consciousness, you immediately start to experience the world. You hear your phone alarm blaring next to you, you feel the soft covers on your body, you open your eyes to the familiar sight of your bedroom ceiling. As you climb out of bed and go about your day, you continue to take in the world through your senses. Your five senses—vision, hearing, touch, smell, and taste—provide all the information you have about the world around you.

But what if I told you that the world you perceive isn’t actually real? That you’re living in a virtual reality created by your brain?

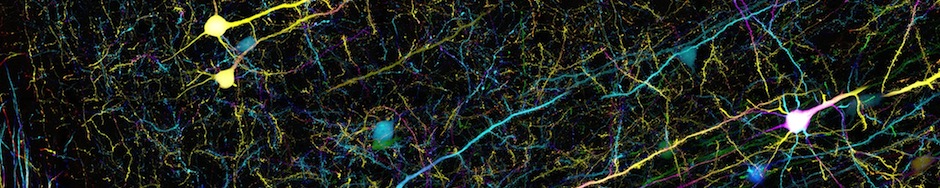

Our brains, like those of other animals, have evolved ways to to collect information about the world around us. We’ve evolved funny-looking contraptions on our bodies, such as eyes, ears, and noses, to acquire specific channels of information which we call our “senses”. This sensory information is interpreted by the brain to create an internal representation of the external world.

The thing is, our internal representation is just that—a representation. It’s not real. It’s not an accurate reproduction of what the world is really like.

And it’s not meant to be. Our brains don’t care about producing an exact image of the external world, because there are many features of the world that aren’t that important to our lives. Instead, our brains create a biased representation of the world that emphasizes features that are important to our survival and neglects or ignores the rest.

More than meets the eye

Take vision, for example. You might imagine that your eyes are like cameras, simply detecting the intensity and color of light at every point in your visual field, allowing you to reconstruct the scene in front of you. But that’s not how the brain works.

Sure, vision starts by detecting light at each point. But then this information is processed by your visual system, which is specialized for recognizing and enhancing specific visual features from the image. Even within the eye itself, there are neurons that are specially designed to enhance the contrast between light and dark edges and to detect changes in light intensity rather than light itself.

As this visual information flows through your brain, it sequentially recognizes visual features such as lines, shapes, movement, and even complex objects such as human faces. (See this post for more.) That’s right—there are neurons in your brain that are activated when you see a human face, and some of them only respond to specific human faces, such as the sight of your grandmother.

Cameras don’t do this. Cameras simply provide a visual reproduction of the world before them. Your brain, on the other hand, creates a warped picture of the world, emphasizing important features such as lines and faces. It’s more like Photoshop than a camera.

Tricked by the brain

We usually don’t notice the distorted images that our visual system creates. But occasionally these distortions are super obvious and make us see things that aren’t really there: illusions.

Here are a couple examples of visual illusions:

This static image looks like a GIF, but it’s not! The rotating circles are an illusion. (Credit: A. Kitaoka)

The checker shadow illusion: square A appears darker than square B even though they’re exactly the same shade of grey. They are, I promise! (Credit: E. Adelson via Wikimedia Commons)

While visual illusions are the most common, there are other types of illusions as well. For example, the old San Francisco Exploratorium had an exhibit featuring the Thermal Grill Illusion (not sure if the new museum has it too). You touch a metal pole that has alternating cold and warm spots. The cold spots are pretty cold; the warm spots are pleasantly warm. But when you grasp a section of the pole with your entire palm, encompassing both cold and warm spots, you feel like your hand is on fire! This illusion reveals how your tactile system distorts reality when it integrates information about cold and warm stimuli, accidentally activating a pain pathway.

Contrary to what you might think, illusions don’t mean your brain has gone haywire. Instead, illusions reveal that your brain is constantly distorting reality and filling in gaps. In reality, our entire experience of the world is an illusion.

The invisible world

Illusions occur when we perceive things that aren’t really there. Conversely, there are a lot of things out there, in the world, that we can’t perceive. These invisible phenomena again reveal how our perception of the world doesn’t reflect reality.

Again, let’s start with vision as an example.

While humans can only see light wavelengths from about 400 to 700 nm, other animals can see light with longer wavelengths (infrared) or shorter wavelengths (ultraviolet).

What a mouse looks like with infrared vision. (credit: Julius Lab via Nature News)

Light is a wave that has different wavelengths, which we perceive as different colors. We humans can see light wavelengths from about 390 nm (purple) to 700 nm (red). We narcissistically call this range the “visible spectrum”, even though different wavelengths are visible to different animals.

Snakes can see infrared wavelengths, generated by body heat, which helps them capture prey at night.

Some insects and birds can see ultraviolet light. This means that parts of the world look totally different to them.

How a flower looks with normal human vision (left) or ultraviolet vision (right). The patterns that are visible in ultraviolet light may help guide insects to the pollen at the center of the flower. (credit: B. Roslett, Science Photo Library)

And it’s not just vision. For example, plenty of animals hear sounds we can’t hear, like ultrasonic frequencies. That’s how dog whistles work, and bats use ultrasonic frequencies for echolocation.

Mice and rats also use ultrasonic sounds to communicate. Every time I’m waiting in a seemingly quiet NYC subway station, I imagine that the room is squealing with the ultrasonic calls of subway rats chit-chatting with one another.

Our virtual reality

So we sense only a small part of the world, and what we do sense is highly distorted. It’s not a faithful representation of the world, but a virtual reality that our brains create for us. And despite coexisting on the very same Earth, every species perceives its own reality. That’s pretty cool.

I have a lot more ideas and examples related to this topic, so stay tuned for my next post if you want to learn more!

So, how do we know what is real then?

take the red pill?

I took the red pill and threw up and it seem like my dog was trying to talk to me

Yes I want to hear more!

Yay, thanks for reading… part 2 will hopefully be up this weekend!