Hey all, this is Part 2 of my list of 10 things I wish I knew when I started my postdoc.

Here’s a recap of #0-5, which you can read more about here:

- Your job is to get another job

- Try to get your own funding

- Cultivate collaborators and/or co-mentors

- If things aren’t working out, switch labs sooner rather than later

- The clock is ticking

- Have a life

#6-10 are below. To reiterate my disclaimer from Part 1, remember that this is my personal perspective and may be somewhat specific to postdocs in neuroscience or other biological sciences.

6. Choose a good project

Ok, so it’s not that when I started I didn’t know I should choose a good project…. but in retrospect I didn’t fully understand what that means. Of course, opinions vary on what constitutes a “good project”, so people may disagree with me, but here’s my view: a good postdoc project should have the right balance of being both exciting and feasible.

An exciting project means that your anticipated results would represent an important advance in the field. Imagine your future self giving a talk at a conference about these results. Do people’s faces light up with interest? Or are they thinking, “eh, this is just some specialized niche thing that I don’t care about”?

In the best case, you’d choose a project that would be exciting no matter what the results are—e.g. distinguishing between two models that are both interesting. I know, most projects aren’t like that. But at least try to anticipate all the possible results you might get, which of them would be exciting, and how likely you think they are.

A feasible project means that you think the experiments will generally work. Your project is probably feasible if it relies on established techniques or builds on preliminary data. Ambitious postdocs are often enticed by exciting, less feasible projects, like developing a brand-new tool. While these projects are critical for scientific progress, they’ve also been many a postdoc’s downfall. If you choose to take on this kind of high-risk, high-reward project, you probably want to have a second, less-risky project as well.

Regardless of your project, there’s always a chance it’ll completely fail. Just make sure that doesn’t translate into a failed postdoc. Have a backup plan. Have a second project, if that’s possible without spreading yourself too thin. Make a timeline for evaluating your progress, and set a deadline for when to switch projects if things aren’t progressing. And don’t be afraid to switch! In an ideal world we could all just do good science without worrying about time pressure, but remember tip #4: the clock is ticking.

7. Embrace the opportunity to learn new things

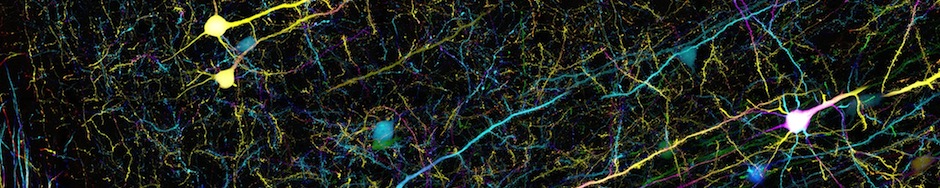

As I wrote in this post on how to choose a postdoc position, you want to learn new things during your postdoc. I set out to learn new techniques like in vivo brain imaging, anatomical tracing, and new behavioral assays. I was prepared and excited to learn these things.

However, I was NOT prepared for all the other things I’d have to learn. Modern neuroscience relies more and more on engineering and programming, things I hadn’t been taught at all during my education as a biologist. I had to learn how electrical circuits work, the difference between analog and digital signals, what DAQs and Arduinos are, how to solder things, and how to program in multiple languages to control all this equipment and analyze my data. And this doesn’t include all the legwork involved in designing the system and figuring out which parts to order, where to order them from, and why there are 16 different versions of what looks like the exact same part.

I was pretty annoyed at having to learn all this stuff. “Dammit Jim, I’m a biologist, not an electrical engineer!” But in retrospect, it was super useful. Having those skills makes me a way better neuroscientist and way more prepared to set up my own lab, if I am ever so fortunate.

True, it would’ve been nice if I’d been able to get more help instead of figuring out so much on my own (e.g. googling “what does DAQ stand for” or watching YouTube videos called “how to solder”). It’s definitely better to get help if you can. But if you can’t, remember that figuring stuff out on your own is the most important skill in research. Practicing that skill will make you better at it.

credit: phdcomics.com

8. Learn to manage and mentor people

Managing and mentoring people is probably the most important part of running a lab. Yet many new PIs have never done it before! Not surprisingly, these people often struggle with it, meaning their labs struggle as well.

That’s why it’s important to get experience mentoring people as a postdoc. I know, most of us try to avoid getting stuck with an undergrad or rotation student—it’s a big time investment. But it’s super important in developing yourself as an independent scientist ready to run a lab.

You need experience training people to do experiments and analyze data. How closely should you monitor them? What should you do if they make a mistake? You can get advice from other people, but I found that I had to figure these things out myself through trial and error. Your mentoring style isn’t the same as everyone else’s, and different mentees require different strategies.

You also need to train yourself to trust your people’s results. Initially this was really hard for me, especially when the experiments require subjective scoring. But over time I learned what kind of controls and quality checks to insist upon so that I could make sure the data was sound.

As you gain mentoring experience not only will you become a better mentor, but hopefully your people will generate data that furthers your research. You’ll also learn how to help your mentees achieve their own goals, so it’s a win-win!

9. Start formulating your long-term goals

As you go through your postdoc, start thinking about what you want to do in your own future lab. Any time you have a random idea for an experiment or question that might be interesting, write it down! I started doing this at some point, and a few years later I was surprised to find that I had several pages of ideas (most of which I’d forgotten about) that could probably sustain an entire lab.

But random ideas aren’t enough. Sift through your ideas and see whether there’s an overarching theme that defines your research goals. This will be super important when you apply for jobs. As a job candidate, you need to define yourself and your research goals in a pithy way, almost like a slogan. And it has to be different from your current lab’s slogan. Otherwise hiring committees will think you’ll be competing with your advisor when you leave.

Your niche can be similar to your current lab’s research as long as there’s some key difference—e.g. using the same techniques to study a different question. Try to come up with something exciting and cutting-edge, not just a modest extension of what you’ve already done.

This isn’t an easy process! But it’s easier if you do it gradually over months or years rather than feeling pressured right before you start job applications. I only started thinking about my future plans early on because I was applying for the K99/R00, and it’s only in retrospect that I realized how valuable that was.

Once you have an idea of your future plans, discuss them with your advisor and make sure they’re on board. If you can, start doing a few experiments related to your future goals. This will help provide preliminary data for job proposals and talks. And don’t be afraid to discuss your big ideas when you give seminars or talk informally with people, especially at conferences. You may get helpful feedback, and you’re creating an identity for yourself that’s independent of your PI.

10. Explore other career options

As I noted at the start, the main goal of a postdoc is to get a faculty job. Unfortunately, most of us aren’t going to obtain that goal. So we need to have backup plans, and your postdoc is the time to explore other career options if you haven’t already.

credit: xkcd.com

The first step is talking to people. Some institutions have career panels or networking events for postdocs. Regardless, I’m sure you know PhDs who have left academia. Ask them how they like their new career, what day-to-day life is like, and what skills are required.

Start building those skills if necessary. Teach a class, practice science writing, take an online programming course—whatever you think might help bolster your skills and resume. Your institution may also offer professional development workshops on topics like leadership and management.

Most importantly, try to find other careers that you might be passionate about. If you truly love science, then you should be able to find other fulfilling ways to engage with science. Or if you want to get out of science completely, that’s cool too.

If you find that you’re not really passionate about any other career, don’t despair. Most people aren’t lucky enough to get to pursue their true passion as a day job. I mean if I really had my choice, my dream job would be to spend my days running and hiking in the mountains. But yeah, that’s not really a job.

A job that’s just “fine” can be perfect if it has the right environment, perks, and hours to allow you to enjoy life more generally. Honestly, most people who have left academia seem pretty happy, often happier than PIs.

Just figure out what makes you happy in life. And remember, work is not life.

Have more tips for navigating a postdoc? Leave a comment below!

Thank you so much for succinctly summarizing “the most important” things a postdoc should know. I am also slowly appreciating the fact that “work is not life”.

I just want to thank you. These are helpful!

Glad to have read this in my first year as postdoc, helps me strategize and evaluate! Thank you!